POSTS

Missed the Boat

Thoughts on The Legend of Zelda: The Wind WakerI was a hater. Everyone loved The Wind Waker when it was released back in 2003, but I belonged to the grumpy minority who disagreed with the cel-shaded art direction. It was fashionable1, and it felt a little trendy to be adopted by a franchise with an established look. Never mind that there had been just one three-dimensional interpretation of the Legend. I’d spent hundreds of hours growing up with Link, and I thought that made me an authority about the way his story ought to be told. So hater that I was, I folded my arms and waited for Twilight Princess.

It’s a shame, though, because I would have loved it back then.

Two decades and two re-releases later, I finally decided that I’d missed something important. The series’ art direction eventually swung back to cel-shading with 2017’s Breath of the Wild, but that wasn’t what changed my mind. I’ve just become less interested in precedence and more interested in artistic risk-taking.

Visuals

I gotta say, judged on its own merit, The Wind Waker is gorgeous. Environments embrace the cartoon aesthetic, with bold lines and vibrant colors supporting simple textures. Tiny flourishes further enhance the visual language, from puffs of smoke, ocean spray, and floating embers. The lighting engine is expressive and supports the adventure’s dramatic sunsets, blustery storms, and enchanting twilights. Character design is imaginative yet consistent, with most of the world’s inhabitants sharing a certain playful quality. It’s all perhaps deceptively advanced to my eyes in 2022–the animation falls short of the bar set by the environment, and non-player characters sometimes betray the game’s age when they loop short, repetitive actions in scripted sequences.

But for all the hand-wringing I’ve done over The Wind Waker’s graphics (and for all the tech that went into those graphics), they may be the least interesting of the game’s noteworthy aspects. The thematic elements and the gameplay both call for some analysis.

Themes

Although it offers little in the way of story, The Wind Waker nonetheless includes a couple motifs worth mentioning.

First of all, it distinguishes itself by celebrating Link’s boyhood. Ocarina of Time may have been the first game to depict Link as a pre-teen, but it was just narrative prelude for “Adult Link.” In The Wind Waker, childhood isn’t a stepping stone toward greatness; it’s a station worthy of empathy. I’ll admit that this took some getting used to. Even after dropping my cel-shading grudge, I was still looking to assume the role of a heroic figure. You do not feel grandiose solving puzzles motivated by your diminutive stature.

Image: Nintendo

Image: Nintendo

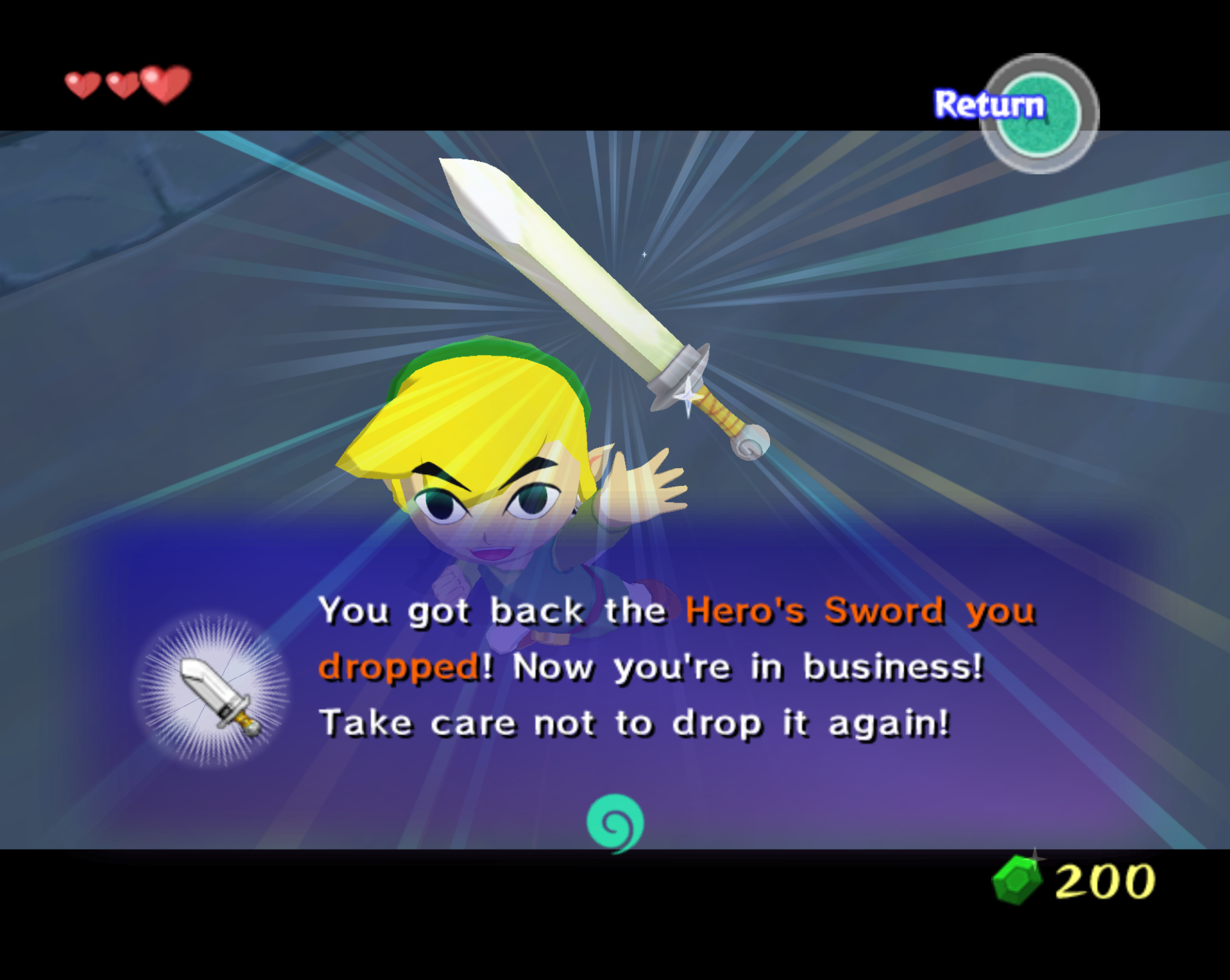

This isn’t an isolated incident: the game never lets you forget that Link is a little boy. He jumps for joy after defeating monsters; he makes the cutesiest squeaking sounds while crawling through passages; he cocks his eye mischievously when sidling along walls. As noted earlier, the monster designs are whimsical and borderline goofy. With the exception of the characteristically-terrifying ReDead, they come across less like nemeses and more like playthings. And while The Legend of Zelda typically uses a neutral voice to describe new items, the text in The Wind Waker is decidedly playful.

Image: Nintendo

Image: Nintendo

It all felt gimmicky and inappropriate for the franchise, but after years of leveling that same judgement at the graphical style, I was content to just roll my eyes and press on. The Master Sword changed my mind.

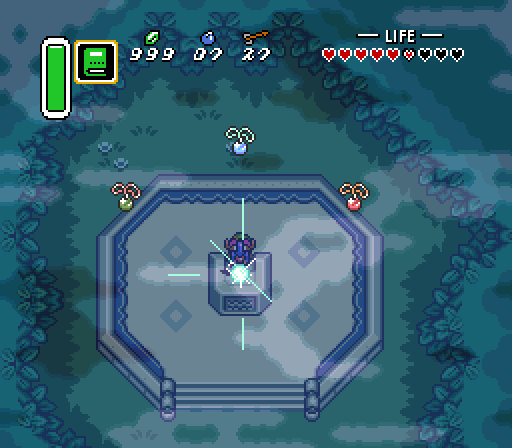

Most games in the series emphasize the legend behind the Master Sword. Its acquisition is a turning point in those stories since it confirms Link’s role in prophecy, and the moment is often among the games’ most dramatic.

Image: Nintendo

Image: Nintendo

The Wind Waker undercuts this reverence, barely mentioning the sword (and even then, only as “the item”) before it’s actually in your hands. Worse: the thing’s busted. Emphasizing the mundane in the iconic weapon was risky, riskier even than flooding all of Hyrule. From that point on, I recognized the game’s prosaic and childlike aspects to be commitment to a new theme for the series. It didn’t inspire much emotion, but it at least deserves respect.

On the other hand, it’s tough to see wisdom behind Tetra’s story. A pirate who reluctantly helps Link in his quest, Tetra soon discovers that she is in fact an embodiment of the legendary Zelda. At this moment, her swashbuckling garb magically transform into royal vestments, and her skin becomes a few shades lighter. She remains in this form for the rest of the game, returning to her authentic self only for the closing sequence.

Image: Nintendo

Image: Nintendo

If I had to guess, I’d say the creators felt such a dramatic change was necessary because they pulled a less racially-fraught version of this trick on Ocarina of Time players just a few years prior. I have no guesses about why they felt the princess’s complexion is an unassailable aspect of her identity.

An isolated event–even a disturbing one–doesn’t qualify as a “theme,” but it’d be reductive to compartmentalize the transformation that way. It’s the game’s only instance of character development, and it concerns the titular character: the one who the player fights to rescue during the third act. The game really had to get this right, and whitewashing was precisely wrong.

Gameplay

Any flagship Zelda game needs solid combat. The Wind Waker has solid combat. It barely changes the system pioneered by Ocarina of Time, but that’s fine–it’s a good system! Boss battles are engaging, and the final encounter with Ganon includes a particularly-memorable team-up with Zelda.

The reward system, on the other hand, really went off the rails. For your efforts exploring the game’s world, you’re most likely to earn… cash. This is underwhelming during the first half of the game since your funds quickly exceed anything you can buy. It becomes downright discouraging when you learn the true purpose: unlocking pieces of the Triforce. In a disappointingly-capitalist twist for the series, The Wind Waker makes the accrual of wealth a necessary component of advancement.

This would be bad enough, but The Wind Waker twists the knife by gating so many prizes behind vouchers. Instead of awarding you with money directly, many chests contain “treasure charts”–abstract diagrams of where you can find sunken treasure on the world map… That is, if you feel it’s worth your time to go dredging in some remote part of the ocean. Fortunately (see what I did there? With the pun? Ah, you’re no fun), this era of Hyrule is almost as flooded with rupees as it is with seawater, so you can ignore this part of the game and still buy your place in destiny.

The Wind Waker even manages to devalue the functional items by throwing them at you with breakneck speed. That’s a problem even if you don’t share my weird brand of fastidiousness (e.g. even if you’re capable of opening a new breakfast cereal before finishing your last) because it cheapens the puzzle mechanics. Typical Zelda games encourage players to experiment with their entire inventory to deduce novel applications. In this game, solutions are instead based largely on the novelty of the newest item. The Skull Hammer is good for smashing stuff and nothing else. With three distinct uses, the Iron Boots fare slightly better, but even they feel poorly-imagined: dive into some water with them on, and rather than drag you down (a mechanic established by Ocarina of Time), they’ll be inexplicably removed for you.

The Wind Waker itself doesn’t necessarily suffer from this problem, but it’s cumbersome as hell. It claims a slot in the “action” menu despite having no value in combat. That’s most apparent during seafaring sequences, where you’ll find yourself juggling it with other items as you navigate and defend yourself. And although issuing commands by playing catchy melodies might sound intuitive, the controls don’t map coherently to directional input.

Image: Nintendo

Image: Nintendo

Mostly, though, the Wind Waker is just slow. It takes time to conduct a sequence, more time to hear complete melody, and still more time to watch the subsequent cutscene. It’s a lot of ceremony for routine tasks like seafaring and controlling NPCs. Apparently acknowledging this, Nintendo later obviated the Wind Waker for navigation by adding a “swift sail” to The Wind Waker HD. Probably I should have played that one, instead.

Child’s play

This review would be a whole lot more positive if I’d been willing and able to play The Wind Waker at the time of its release. At sixteen, I definitely would have felt older than Link, but I still would have enjoyed some amount of wish fulfillment (rather than mere intellectual appreciation). My gameplay sensibilities were also different back then. I have only fond memories for Heroes of Might and Magic, and if the moon’s in the right phase, I can almost feel the craving for the sparkling treasure chests that so enthralled me in grade school. Hunting down sunken prizes in three glorious dimensions would have felt dang satisfying to young Mike. And because I wasn’t especially critical of the media I consumed as a kid, this game’s bigotry would have slid by me unnoticed.

As a grown-up (ostensibly), I’m less than inspired by these aspects. They’re enough to drag down the game’s many strengths, and they make it hard to recommend to a general audience. Players with good imaginations, lots of patience, and limited expectations for substance will probably enjoy The Wind Waker. For everyone else, though, this installment may be the best one to skip.

-

The console games that immediately come to mind:

- Jet Set Radio (2000), sale data not available

- Fear Effect (2000), 720,000 copies sold

- Cel Damage (2001), 120,000 copies sold

- Fear Effect 2 (2001), 180,000 copies sold

- Jet Set Radio Future (2002), 210,000 copies sold

- XIII (2003) 570,000 copies sold

- Viewtiful Joe (2003), 321,000 copies sold

- Killer7 (2005), 150,000 copies sold