POSTS

"You will know soon how I feel"

Thoughts on the 2009 anime series Monster by Naoki UrasawaI was fortunate enough to learn very little about Monster in the wake of the anime’s highly-acclaimed release between 2009 and 2010. I only knew it was a fictional drama and that it depicted a lot of suffering. If you’re similarly uninformed, I strongly recommend that you quit reading here and go give it a shot. Like a lot of contemporary fiction, Monster is best experienced with as few preconceptions as possible.

…but it’s a lazy critic who says “trust me,” and an imaginary audience who complies. I’ll justify my recommendation with some broad (and spoiler-free) praise and say a bit more about the sensitive content. After that, I’ll get into grounded (and spoiler-full) synopsis.

“He’s suffering in an abyss of sadness.”

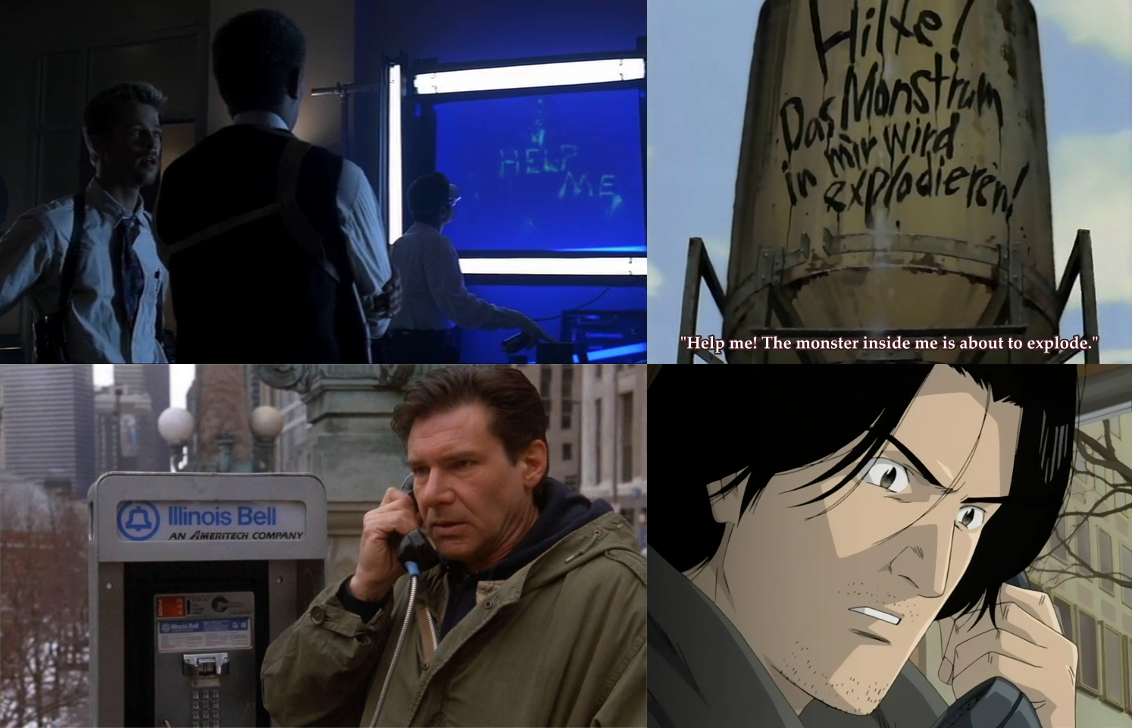

Monster is as thrilling as 1993’s The Fugitive and as unnerving as 1995’s Seven. To say that it shares elements from both would be an understatement; it’s more accurate (and more exciting) to imagine writer Naoki Urasawa smashing the films’ premises together.1 He did more than that, though: he made the setting matter, and he somehow crammed in even more emotion. I don’t make these comparisons lightly; The Fugitive and Seven are two of my all-time favorite films.

Images: New Line Cinema (top left), Warner Bros. (bottom left), Madhouse (top right & bottom right)

Images: New Line Cinema (top left), Warner Bros. (bottom left), Madhouse (top right & bottom right)

That said, plenty of folks will need to know more about those “depictions of suffering” before making up their mind. Here’s a more specific content warning, roughly ordered from most- to least-prevalent: brainwashing, murder, child abuse, schizophrenia, PTSD, drug addiction, suicide, torture, terrorism, and rape.

Rest assured, though: Monster does not delight in trauma. I’m not qualified to differentiate between tragedy and sadism in art, but I can at least explain why I feel comfortable publicly lauding a cartoon which includes such terrible themes. Essentially, it respects the seriousness of each offense. Urasawa’s preference for indirect depiction, while hardly softening the blows, demonstrates his aversion to sensationalism. To be sure: the series does get graphic, but it does so sparingly and intentionally. The statements it makes about the human condition would be incoherent without authentic depictions of pain.

“Her name doesn’t matter.”

Monster’s popularity could be explained by its masterful storytelling alone. The score, while every bit as desolate and violent as the action it supports, is also restrained. Some of the series’ most dramatic sequences are oppressively quiet. The cinematography is likewise understated, though somewhat more thematic (I’m thinking of how regularly Kenzo Tenma is framed across reflective surfaces, or how Wolfgang Grimmer is identified through his smile). And although you only need one hand to count the number of Japanese words I know, the strength of the voice acting transcends the language barrier.

Monster knows how to depict troubled people. You meet so many characters who are struggling internally as the main storyline unravels. Some of them come and go without too much examination (e.g. Dr. Schumann or the teenager practicing medicine without a licence), but a good number receive the time and attention necessary to inspire empathy:

- a recovering alcoholic who struggles with temptation and post-traumatic stress

- a jaded henchman surprised by his own optimism

- a dedicated attorney who can’t confront his family’s history

- a criminologist who works past his grudges

- a student who harbors conflicting feelings about his delinquent father

- a seasoned inspector who stubbornly rejects nuance in his work and his life

- a victim of child abuse who desperately wants to feel human emotion

- a stunted detective who grapples with adulthood and the stakes of his profession

And that’s not to mention Nina Fortner and Tenma, whose stories envelope the series. Before long, the mere introduction of a new person becomes an exciting event, and the directors seem to know it. There’s an almost winking tone in the dramatic flair they apply to the entrance of some characters, as if to say, “wait till you get a load of this one.”

The depth of exploration into some characters makes even relatively flat ones seem authentic. We don’t hear much about Reichwine or Lotte, for instance, but this doesn’t feel like a failure in writing. Just as in real life, not everyone is experiencing a personal crisis at all times. Even Tenma benefits from this treatment; for all his time on screen, we get only the briefest glimpse of his life before the opening sequence. It’s simply not relevant.

Unfortunately, a couple characters experience transformative change with very little examination. The unnamed orphan forgives Hugo Bernhardt for killing her mother after a hasty montage of frosty cohabitation. Dieter’s triumph over behavioral programming feels even more rushed. On the one hand, two shallow developments out of a dozen or so rich ones seems like a pretty good score. On the other hand, the series had the time (ostensibly) and the emotional capacity (demonstrably) to give these characters their due, so the brevity feels like a missed opportunity.

The storytellers also have a light touch in the portrayal of social interaction. In one of my favorite episodes2, Mr. Rosso (an old restaurateur) asks Nina (his teenaged employee) about her interest in guns and marksmanship. It’s a simple exchange on paper, but you can feel both of their cautiousness giving way to trust, even as you sense that Rosso has more to say. Not many exchanges are as laden with subtext as this one, but just knowing that the creative team can pull it off makes watching the events unfold that much more compelling.

More than anything else, though, the series excels in pacing. It’s packed with great twists, making for a deliciously disorienting first experience. It’s not all about cliffhangers, either–the creative team keeps viewers on their toes by occasionally revealing these turns in the middle of an episode. For a talky drama like Monster, action sequences are a sort of twist, and they likewise pop up unexpectedly (they’re also the most intricately-animated moments in the series).

Animation: Madhouse

Animation: Madhouse

It’s not all about the thrills, of course. In a logical extension of the care given to individual characters, Monster takes time to fully develop subplots into meaningful stories of their own. I all but forgot about Tenma’s plight while watching Karl covertly size up his long-lost father. Likewise, the cautious emergence of affection between Eva Heinemann and Martin Reest is a movie unto itself. These plots sometimes rests on unbelievable coincidences (often related to Tenma’s abilities as a physician), but they’re rarely garish enough to break the suspension of disbelief.

“I must kill that man.”

So far, I’ve mostly been concerned with how the anime tells its story. That wouldn’t count for much if it didn’t have anything meaningful to say. Monster has plenty, but two themes struck me the hardest: its reflections on malice and its exploration of duty-bound violence.

Many of the stories in Monster explore the ways people are driven to harm others. We see xenophobia and perverted altruism in all the people who assist Johann Liebert, expressed through eugenics, racism, and terrorism. Urasawa gives these villains the least consideration, perhaps dismissing their ignorance as uninteresting. Contrast that with his treatment of Martin, who despises everyone equally. Through Martin, we learn what can inspire misanthropy and the kind of aggression it can induce. Through Eva, we consider how people misdirect their own self-hatred. Through Heinrich Lunge, we can almost feel self-righteous punitive rage.3 Through Johann, we experience pure evil. Many viewers rank Johann among the most effective depictions of evil in fiction and with good reason: it’s explained by the chaos of his childhood, evinced by the atrocities he orchestrates, and presented in unnervingly gentle dialog.

One can get lost in detail with a work so layered as Monster, but the most overt and consistent theme is also the most brilliant: the reluctant vendetta.

Nina and Tenma hold love and peace as central to their being, yet they both feel uniquely responsible for Johann’s crimes. They recognize that the monster cannot be reasoned with, but they can’t escape the contradiction in their mission. “I’m not a doctor anymore!” Tenma yells at Grimmer. In a setting bursting with people on self-righteous missions, Nina and Tenma alone struggle with their convictions. Monster is the story of how this all but destroys them.

In episode after episode, the two are bombarded by atrocities which affirm their duty. Just as often, they meet people who speak to their fundamental peaceful nature. Nina, through her shared history with Johann, struggles with the desire to remain ignorant as repressed memories of her victimhood repeatedly overwhelm her. For his part, Tenma bears the weight of a hypocrite as he advocates for peace to those around him, many times over. The prolonged anguish takes a physical toll on Tenma; he looks like a different person by the finale. More subtly, obsession manifests in both Tenma and Nina through their neglect of the hair that falls across their faces.

Image: Madhouse

There’s something particularly intense about Tenma’s despair. Although tragically pervasive, it never crosses into melodrama. Urasawa’s greatest achievement is bringing viewers into the doctor’s contradictory state of mind. For all his training and outrage, he is never ready to fire a weapon. This would be maddening to witness were his state of mind not so expertly conveyed. Tenma’s a far cry from Evangelion’s Shinji Ikari, though; his hesitation feels dreadful, even agonizing. You need Tenma to succeed, but you can’t stand to see him kill.

“I learned how to make my face in the shape of a smile.”

Monster is the longest anime I’ve seen, and it’s also the most dense. There’s very little fluff in those 74 episodes. That’s made it hard to be succinct–even in these overlong “thoughts,” I’ve barely mentioned some of my favorite characters. Like some kind of otaku breakup, the conclusion inspired a sense of loss in me.

I can hardly fault the series for this, though. The finale hit all the right notes: it tied up a bunch of loose ends without feeling contrived, and it offered tons of emotional payoff.

So this “problem” might feel familiar to anyone who’s enjoyed a substantial and consistently-engaging story. Maybe I’ll try to write about Richard Brown or Lunge or Grimmer separately, or maybe I’ll check out the manga. Even if I never see another one of Urasawa’s works (unlikely at it seems at this point), I’m sure I’ll be revising my take on Monster for years to come. I couldn’t ask for more from any work of fiction.

-

Though this is only illustrative; the manga predates Seven. ↩︎

-

Episode #15, “五杯目の砂糖” / “The Fifth Spoonful of Sugar” ↩︎

-

More than any other character, Lunge deserves an essay of his own, but here, I’ll only highlight the fastidious restraint with which he subdues his own emotions. For reasons I’d need yet a third essay to explain, this made Lunge the most compelling character for me. ↩︎