POSTS

Chaotic Good

Thoughts on Alan Wake from Remedy EntertainmentAlan Wake is one of a few titles whose seemingly-universal acclaim left an impression on me that survived an entire decade without gaming. Like Mirror’s Edge, I knew only just enough to sustain a hazy, idealized anticipation. “I’m going to love that some day,” my subconscious predicted, “whatever it is.” Having just completed the game along with its two “special features” and subsequent spin-off, I’m satisfied to find my hunch was correct, though I’m also surprised by how flawed the works are.

It’s the best television series I’ve ever played. At its best, it successfully emulates the qualities that made shows like The X-Files so successful. I’m not talking about the cosmetic similarities, though it’s true that each act concludes with a cliffhanger followed by a title sequence followed by a recap where Wake actually says, “previously on Alan Wake…” Appropriating such a familiar format would be gimmicky and unremarkable if it weren’t for the more substantive parallels to serialized television.

For one, it’s thrilling as all get-out. Remedy honed the combat system to a razor-sharp edge: your abilities are simple but tight, granting a strong sense of control without getting bogged down by tactics. Victory feels rewarding and defeat feels fair. In place of the depth typically afforded by large arsenals and fancy maneuvers, novel constraints keep the fighting feeling fresh through the entire experience. While many encounters boil down to a rapid succession of fight-or-flight decisions, you also find yourself supporting an NPC with only flares, brawling with a thresher in a field, and rushing your objective with assistance from a helicopter-mounted flood light. You’ll even hop in a few vehicles, where you’ll find the physics engine and control scheme do a surprisingly-competent job (though my standards may be low–in my experience, video game driving sequences are usually chintzy and annoying distractions).

Great pacing supports the tension. By moving briskly through varied environments, interspersing meaningful dialog in a variety of formats, and punctuating it all with confrontations with the possessed townsfolk (a.k.a. the Taken), Alan Wake consistently feels invigorating. Generous checkpointing directly supports rapid progress by severely limiting the ground you have to retread following failure. More subtly, in making this mechanic completely implicit (you can’t manage your save states, so forget about save scumming), the designers created a framework that necessarily restricts the impact of player choice. In other words, Alan Wake has to be very forgiving because it welds shut every door you enter. For instance, despite insinuating a scarcity of ammunition, the game doesn’t truly require resource rationing. Once you recognize that “run and gun” is a safe strategy, the pace increases yet again. Folks looking for a immersive sim with meaningful choice will be supremely disappointed, but we’re playing a TV show, here!

Alan Wake is also as intriguing as any monster-of-the-week television. The Taken are bizarre yet threatening, the Darkness is nebulous and foreboding, and Thomas Zane is an inscrutable ally.1 It’s structurally self-referential, with the narrative being influenced by Wake himself and regularly foreshadowed through manuscript pages penned by Wake prior to an episode of amnesia. My favorite example comes when agent Robert Nightingale, a modern-day Javert, discovers a page about him:

He took out his hip flask when he reached the page that described how he reached the page that made him take out his hip flask.

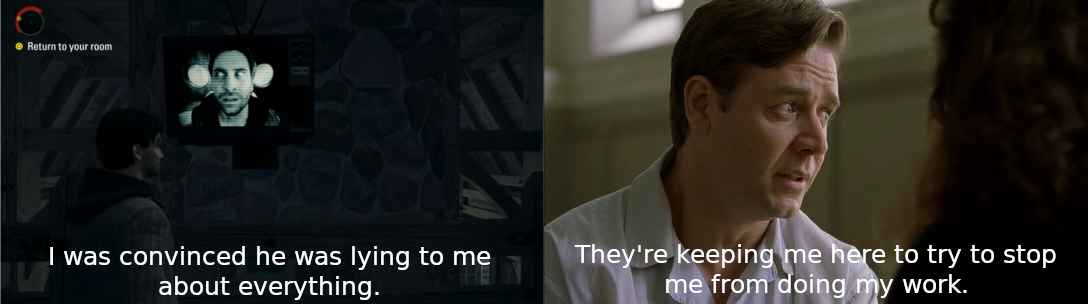

The manuscript pages are fascinating because they represent a character trying to surreptitiously control his own fate, a premise only further complicated by the suggestion of schizophrenia (not to mention Alan’s vocal skepticism of his own perception).

Images: Remedy Entertainment (left), Universal Pictures (right)

Images: Remedy Entertainment (left), Universal Pictures (right)

The game supports these more cerebral qualities with gorgeous aesthetics. Visually, it’s aged better than any other game that qualifies as a “teenager,” particularly considering its ambitious woodland locale. As the central motif, light gets a lot of attention, and the engine is more than capable of supporting the focus. Most of my screenshots (not to mention my travel photography during the time I was playing) concern the way environments are lit. Signal flairs make the most striking example; their intense red glow washes out all other color and heightens the urgency of the situations that require them. Sonically, Alan Wake boasts one heck of a soundtrack. The score is really pretty though I admittedly only recognized that retrospect. Probably I was too focused on the pop songs which accompany the aforementioned interstitials. Beyond the star power on display2, the selection is almost Tarantinian in its fitness for the mood. It even includes a few tracks written just for the game, each featuring narratively-relevant style and lyrics, and each catchy in its own right.

For all its success emulating a great television series, it’s interesting that Alan Wake generally flounders more like a mediocre action movie. The linearity I was praising earlier proves itself to be a double-edged sword when you start to feel like a simpleton muscling your way through every obstacle. The overly-helpful UI obliterates any hope of feeling clever (with a compass giving almost step-by-step direction and an ever-present text description of your current task), and Wake vocalizing the most obvious suggestions doesn’t help.3 While Wake himself is ultimately redeemed as a compelling protagonist–flawed yet capable of growth, the same can’t be said for any of the supporting cast. Finally, just like a puerile action flick, Alan Wake’s conclusion is murky at best and devoid of any coherent thesis.

I thought I had the game pegged by the time I reached the “special features” which Remedy released as two installments. It seemed fun and polished but also safe and forgettable. My experience of video game “downloadable content” suggested that these extra episodes would feel all too familiar due to reused art assets, conservative gameplay tweaks, and superfluous plot developments. Boy, was I wrong.

Alan Wake’s special features refine all the strengths of the mainline game. “Now that I knew what I was facing,” Wake narrates, “the environment became even wilder and stranger, like it was no longer even bothering to pretend that things were normal.” What first appears to be a flimsy premise constructed to excuse asset reuse (e.g. a dreamlike return to familiar destinations) quickly proves itself as a sincere and well-supported narrative twist. The environment turns nightmarish, and the gameplay follows suit. It challenges players to only selectively illuminate targets, to brave a valley of flickering streetlights, and to rush through an onslaught of enemies under the intermittent respite of a lighthouse beacon. Wake’s alter ego likewise becomes unhinged and truly frightening to witness. Actor Matthew Porretta had already delivered a great performance as a self-involved and melodramatic writer, but here, the story called for a depiction of Wake in fugue state–surely a fraught proposition for any actor. Porretta takes the risk and comes up a winner; his “psychotic Alan” is full of paranoia and sarcasm and menace.

Wake’s commentary is even more entertaining, as he is reacting to his own subconscious. “An elevator,” he observes, having just crawled through a giant rotating diorama of his life, “Sure, why not?”

These episodes make no effort to address the game’s weaknesses (still incredibly linear, still rife with useless collectibles, and still narratively ambiguous), but I found myself much more forgiving of the flaws in light of the more risky decisions. For me, “The Signal” and “The Writer” were the payoff for a fun-but-unremarkable action game.

Alan Wake’s American Nightmare, on the other hand, messes with the formula and comes out much worse for it. It’s a shame because I generally applaud risk-taking in established franchises. The spin-off includes far more open environments, and I was surprised by how strongly this change evoked Mega Man Legends for me (another title which grants unprecedented mobility unto a familiar character). Unfortunately, in this game, choice only amounts to the path you take on each fetch quest. The conclusion manages to be simultaneously more definitive and less satisfying.4

Image: Remedy Entertainment

Image: Remedy Entertainment

While game has its merits, I can count them on one hand.5 If the original title’s shortcomings feel like a game trying to be a bad action movie, American Nightmare comes off as a bad action movie trying to be a game. This kind of blunder might be expected from a new development house taking the reigns, but Remedy Entertainment made this one, too. I just don’t know why.

Strangely enough, I find myself willing to look past American Nightmare. I may be getting used to botched endings, but that game’s status as “not a sequel” definitely make it easier to ignore. The collection was easily worth the limited time I have for games these days and only marred by a lack of closure. Fortunately, Alan Wake 2 came out this year, and all signs point to a faithful continuation of the polish and the madness.

-

Beyond his dreamlike existence, the game casts some doubt on Zane’s trustworthiness toward the end; I’m disappointed it didn’t explore this thread any further. ↩︎

-

It’s worth noting that a small game company like Remedy was able to secure licenses from the likes of David Bowie, Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds, and Roy Orbison. ↩︎

-

Like when he reaches a closed gate and comments, “I had to find a way to open the gate,” or when he discovers an old wooden boat and muses that it “looks like a battering ram” (the only notable object in the room is a switch which sends the boat careening through a nearby wall). ↩︎

-

It’s not that they key to defeating the antagonist was a set of arbitrary actions–I’m actually fine with that (in my book, mystical bullshit can just be mystical). It’s that the writers offered no explanation as to how Wake outwitted his nemesis, making his triumph feel both abrupt and unearned. ↩︎

-

You meet Mr. Scratch (a new persona of Wake’s), fight some new and strategically-compelling enemies, and receive rewards for collecting items. ↩︎