POSTS

JSHint: Watching the Ship Sink

This is the first essay in a four-part series about relicensing the JSHint software project.

The process of relicensing JSHint took seven years. That’s far longer than anyone expected, but seeing this through wasn’t just a matter of endurance. As I worked with people around the world to move to the MIT Expat license, I regularly experienced how non-free licensing (even as seemingly trivial as “Good, not Evil”) poisons the well of free software.

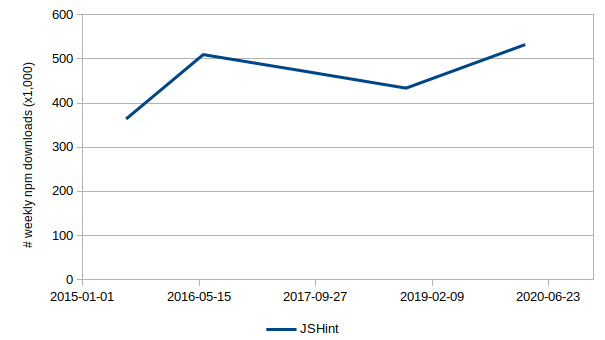

Some numbers might help here. The following graph shows how many times JSHint has been downloaded from npm each week over the past five years:

We had a dip last year, but we’ve since recovered and then some. Over half a million downloads per week sure sounds impressive, doesn’t it?

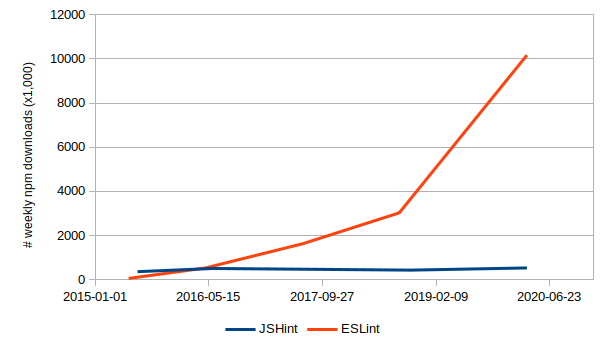

It was impressive in 2015. The fact is, npm’s usage has exploded over the past half decade. Holding steady in this space is actually falling behind. Take a look at the same statistic for ESLint, a truly open source project with the same purpose and target audience as JSHint:

Suddenly that dip in 2019 doesn’t seem so important. How did JSHint go from being the most popular tool in this space to one that most developers today consider antiquated? There are many explanations, but in this essay, I’ll focus on the effects of non-free licensing.

For license-sensitive users

JSHint was partly licensed under the JSON license. It is nearly identical to the widely-used MIT Expat license, but it includes one additional clause:

The Software shall be used for Good, not Evil.

Because of this clause, folks who respect the practice of software licensing simply could not use JSHint.

If you’re not versed in legal matters, that probably seems like an odd restriction. By rejecting JSHint, are people admitting that they want to do evil? And is that clause actually enforceable, anyway?

The answer to the second question is “no,” and that helps answer the first question. Legally-conscious objectors aren’t betraying their own dastardly motivations; they’re refusing to enter into an ambiguous contract. Put differently: they’re not saying, “I’m an evildoer,” they’re saying, “I don’t understand what you want.” This consideration disqualified JSHint from inclusion in all sorts of contexts.

First, there were legally-conscious software repositories. Developers from the

Debian and Fedora

GNU/Linux distributions independently concluded that they could not include

JSHint due to licensing concerns. That’s why Ubuntu

users can’t download JSHint via sudo apt-get install jshint.

Even in less discerning package managers, folks built tools to empower

developers to make similar decisions on their own. For instance, JSHint has

been available on npm since its initial release, but

SPDX (along with tools like

license-report and

Yarn) has since been

designed to help folks understand the legal requirements of their dependencies.

This seemed like an encouraging trend toward conscientious code sharing, so we

did our part by adopting SPDX in

JSHint.

More recently, an instructor at a US university wrote to the JSHint team asking for permission to use JSHint in their course. I replied,

By all means, you are welcome to use the project and its website in your courses. Please note, however, that the source code is partially published under the JSON license. The FSF does not recognize this as a free software license nor does the Open Source Initiative recognize it as an open source license. This detail does not effect most people in practice, but you may want to verify with your legal team before relying on the code base.

Honesty may be the best policy, but it also means fewer people are going to use your bizarrely-encumbered JavaScript linter.

Finally, programming platforms that “repackaged” JSHint have reconsidered that practice because of the license issue. There was a time when the popular content management system WordPress repackaged JSHint in this way. Once they learned of the JSON license, they replaced JSHint in a matter of weeks.

For feature-craving users

Plenty of people don’t give a fig about free software. Whatever their reason, they couldn’t care less about the legal terms that are bundled with publicly-available source code. The “Good, not Evil” clause also pushed them away, even if they didn’t realize it.

It began with the decline in license-sensitive users. The word “user” is a bit too passive in the context of open source tooling because folks who use the software are particularly empowered to contribute back to it. The “user-base” is directly correlated to the “contributor-base.” When a project like JSHint loses users, it also loses contributors.

This slows the addition of new features and the correction of bugs. Timeliness is important for these things, and people perceive delays very negatively. The best example of this comes from JSHint’s delayed support for async functions.

(The async function is a JavaScript language feature which was introduced in 2017. It’s very popular among developers but also very difficult for parsers to implement correctly. It took us over a year to support it in JSHint.).

Some expressed their dissatisfaction with the delay in calm (though somewhat impatient) terms:

Async/await has been at stage 4 for over a month now (and baked into Node and many mainstream browsers for longer), but jshint has yet to add support.

…but others were more emotional:

- “You just lost my interest in jshint. Sorry, to [sic] slow.”

- “Thank you JSHint. It was good while it lasted. Switched to ESLint.”

- “RIP Jshint”

- “Seems like we waited enough. Bye JSHint. It was a good time.”

- “I know that you get a lot of complaints about this, but… if you can’t find

a way to include support for async/await, jshint is useless to me. I’m

switching to just using

node -c <filename>” (via e-mail)

The Internet has a way of surfacing the loudest and angriest perspectives, but it seems safe to assume there was a substantial group of less vocal developers who came to a similar conclusion.

A dwindling user/contributor-base is a vicious cycle. Though the movement may have started with license-conscious folks, everyone felt the pain of the release cycle equally, and their exodus exacerbated the problem.

This isn’t just a story of open-source “market” forces, though. My own management decisions contributed to JSHint’s dissatisfying release cycle.

You see, many people express their dependency on software using a range of versions. They don’t say, “give me Firefox at version 67.02.3” because they don’t really care about that particular release. What they want is the software to be familiar but also secure. They’re more likely to say, “give me the latest version of Firefox 67.” With this statement, they’re trusting the maintainers of Firefox to provide a program that looks and acts a certain way (i.e. not exactly like version 65 or version 68) but that also has the latest bug fixes (so 67.02.4 is preferable to 67.02.3).

This practice generally benefits users and developers alike. In my case, though, I had a conflicting personal goal: I wanted the relicensed version of JSHint to reach as many people as possible.

If we made drastic improvements to JSHint, we’d have to release a new major version. The relicensing effort could continue with the new version, but many people would continue to use the old version. For all the obsessing I’ve done about JSHint over the years, I haven’t forgotten that most people aren’t particularly concerned with the release schedule of their JavaScript linter. When and if we succeeded, the users of the old version would be cut off from our success (not to mention the improvements we made from that point forward).

This consideration made me averse to drastic changes in JSHint. Pretty antithetical for a project maintainer.

Software freedom matters

For many people, licensing is an esoteric part of software development. It’s a relatable opinion: the legal frameworks are intimidating, and most considerations can be addressed by simply defaulting to well-known free/open-source licenses.

The trouble is that not all software is distributed under well-known free/open-source licenses. My hope is that the particulars of JSHint’s decay help folks understand why licensing matters.

After reading the drudgery of JSHint’s slow decline, you might be wondering why we didn’t just give up. A sinking ship is only tragic if you value the ship. If a newer, faster, similarly-named ship sails by, then maybe it’s time to put down the bailer. It’ll take another essay to address that fully.